You were looking for what? (Or, search term questions.) October 26, 2017

Posted by tomflesher in Macro, Teaching.Tags: CPI, Reader questions

1 comment so far

Occasionally I mine the search terms for interesting questions. Here are three from the past month:

- What is an increase in CPI?

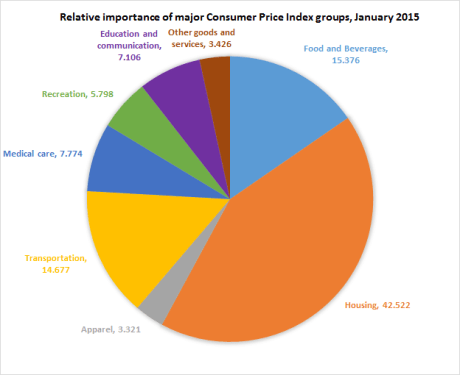

When a country’s CPI increases, that means that, on average, the cost of living in the country has increased. The Consumer Price Index measures the price of a fixed basket of goods. For example, in the United States, CPI consists largely of housing costs, food and beverages, and transportation. When the price of any good in the basket goes up, it increases total basket expenditure, but the effects of (for example) increasing food costs would be greater than the effects of increasing costs of haircuts (included in the “Other” category). Although the BLS is careful to point out that the CPI is not a cost-of-living index, it functions a lot like one. (The chart was retrieved from the US Department of Labor website.)

When a country’s CPI increases, that means that, on average, the cost of living in the country has increased. The Consumer Price Index measures the price of a fixed basket of goods. For example, in the United States, CPI consists largely of housing costs, food and beverages, and transportation. When the price of any good in the basket goes up, it increases total basket expenditure, but the effects of (for example) increasing food costs would be greater than the effects of increasing costs of haircuts (included in the “Other” category). Although the BLS is careful to point out that the CPI is not a cost-of-living index, it functions a lot like one. (The chart was retrieved from the US Department of Labor website.)

The percentage change in CPI, otherwise called the CPI growth rate, is the most common measure of inflation.

- if the cpi went up why not all the goods prices goes up? [sic]

This question gets the causation backwards. The CPI measures how much prices are changing; you can use the percentage change in CPI to measure how much, on average, prices have gone up, but that says very little about individual goods. For example, the Transportation category includes the price of gasoline. If cell phone bills decreased, but gasoline prices increased, the fact that we (on average) spend more money per year on gasoline than on phone bills (as reflected by the different weights, above) means that the gas price increase will have a greater effect on our overall spending.

CPI reflects those changes. It’s possible for the total cost of the basket of goods used to measure CPI to increase even if some of those goods had steady or even decreasing prices.

- mastovesion is good or bad

You do you, gentle reader.

Faculty Freebies and Price Discrimination April 3, 2017

Posted by tomflesher in Examples, Micro, Teaching.Tags: Introduction to Microeconomics, Price discrimination, Principles of Microeconomics

add a comment

Despite its nasty-sounding name, price discrimination is interesting and beneficial to some consumers. (Of course, when we move away from equilibrium to make someone better off , we usually make some other consumers worse off.)

Textbook publishers face a classic case where price discrimination would be useful: they want to charge students high prices for their textbooks, but because professors have the power to require a textbook of their students, they want to get professors on board as easily as possible. That usually means lowering the price of the book for professors (to make it easy to get); I get tons of free books every semester.

Publishers don’t want those free books to get into students’ hands, though – that means either a student didn’t pay for a book because a virtuous professor gave a freebie away, or the student paid, but paid an unscrupulous professor for a book the professor got for free! If a student is going to pay for a book, the publisher would rather get a cut of it.

Goods that are difficult to resell are easiest to discriminate on. Publishers have, for a long time, printed “INSTRUCTOR’S REVIEW COPY – NOT FOR SALE” on books. That has some effect, but you still have the possibility of paying for a book on Amazon or AbeBooks. One way to keep students from buying these books is to sink money into online resources, which are tied to students’ identities. That way, even if the student buys a used copy of the physical text, they still have to pay for access to the online resources. Still, not every instructor uses those, so this isn’t foolproof.

One publisher, Cengage, has taken an additional step with Greg Mankiw’s principles book: not only does it say “Compliments of N. Gregory Mankiw” on the front, along with the usual “Instructor’s Edition” language, it has my name embossed on the cover. “Specifically prepared for” is printed, and “Thomas Flesher” is stamped into the front cover. (Of course, I prefer Tom, but you can’t be too picky with freebies.) This is a pretty clever means to keep me from reselling the book, at least unless I have a high name value. I can easily imagine a student wanting to purchase a book specifically prepared for Dean Karlan or Paul Krugman, for example, if either of them still teaches Principles using Greg’s book. (I doubt it, since each of them has his own.)

Either way, Cengage is trying to protect what’s likely its largest profit-producer by minimizing the number of free copies students can use.

What are discouraged workers? April 9, 2016

Posted by tomflesher in Uncategorized.Tags: discouraged workers, Introduction to Macroeconomics, labor force, Principles of Macroeconomics, Unemployment

add a comment

What’s the difference between these two workers?

Vic loses his job. He looks for work for a while, but eventually realizes there are no jobs available for him. He decides to stop looking.

And:

Todd loses his job. He looks for work for a while, and even when no jobs seem to be available, he keeps looking. He still can’t find a job.

Unemployment rate with and without discouraged workers. Note the spread, which ballooned during the recession.

The answer is clearly that the only difference between Vic and Todd is that Todd continued looking when Vic didn’t. Is that a distinction without a meaningful difference? Not according to economists, who would classify Todd as unemployed because he’s actively seeking full-time work and Vic as a discouraged worker.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines a discouraged worker as someone who looked for work in the last year, but who stopped looking because they think there is no work or that they aren’t qualified for the work available. These workers may consider themselves unemployed, but they don’t qualify for the BLS’ definition of unemployment, which requires the worker to be actively seeking work. Thus, there are a lot of workers who wish they were employed, but can’t find work – but they don’t count as unemployed, because they stopped looking for jobs.

When the economy improves, many discouraged workers move out of that category and into the category of “unemployed” by beginning to look for work. This leads to a paradox: when the economy starts to improve, there are fewer discouraged workers, because they become unemployed instead – so the unemployment rate goes up! For that reason, economists generally take a short uptick in the unemployment rate which follows a long-term downward trend as a good sign for the economy, since it means workers are more optimistic about the economy.

Graph is courtesy of FRED.

How do producers charge different consumers different prices? September 29, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Micro, Teaching.Tags: Introduction to Microeconomics, micro, Microeconomics, Price discrimination, Principles of Microeconomics

add a comment

Price discrimination is the act of charging different consumers different prices based on how much they’re willing to pay. There are a few different forms of price discrimination, and it can be achieved different ways depending on how much information a seller has.

Haggling, or negotiating to find an exact willingness to pay, is an effective form of price discrimination for large purchases. For example, a car salesman can often start with a high price, and when the customer refuses, he can incrementally lower the price (or otherwise adjust the offer) until he find a deal that the buyer is just barely willing to accept. This has one huge advantage – it gets the most that the customer is willing to give up (or, in other words, it extracts the customer’s maximum willingness to pay). It is, however, very costly for a salesman. Just imagine if the salesman were to spend a whole day negotiating only to realize the buyer wasn’t willing to pay enough to cover the cost of the car. Then, the salesman loses the chance to make a sale at all that day. Since it’s costly, this method is most useful for high-priced items like cars and houses.

If you ask a consumer what he’s willing to pay, he’ll lowball you; haggling helps force the price (and the profit) up.

Direct segmentation allows a market to be broken up based on some visible characteristic. In the previous post, I discussed my father-in-law’s senior citizen discount on haircuts and how he pays less than I do for the same cut. He does this by asking for a senior citizen discount, which I’m not eligible for.

Direct segmentation involves breaking the market up into different groups and intentionally charging different prices to those different kinds of people. It works best when one group has a higher willingness to pay – so, since I’m not a college student, and not a senior citizen, my (relatively) high income means I don’t ask for a discount. Similarly, I pay a lower price to have my blazers dry-cleaned than my department chair does, even though her blazers are made up of a smaller amount of fabric. Dry-cleaners just automatically charge a higher price for a woman’s garment than a man’s, even if the garment is similar.

This sometimes leads to unpleasant outcomes. NPR did a story on a 12-year-old girl who had to pay a premium to play Temple Run as a female character; non-white-male characters were all in-app purchases that cost money.

Indirect segmentation is like direct segmentation, but requires the consumer to do some work to get the lower price. A good example of this would be a volume discount. I have a strong preference for Crayola An Du Septic dustless chalk. (I like its weight and erasability.) When I purchase chalk to use in the classroom, my buying options include paying about $3.50 for a single box or about $12 for a 12-box package. No sane person who isn’t a teacher has any use for 12 boxes of blackboard chalk, so I signal my price sensitivity by buying a larger amount at once.

Another way people reveal their types is by clipping coupons. A coupon is like a little badge that says “I’m cheap! Give me a lower price!” By doing a bit of extra work to signal my cheapness, I qualify myself for a lower price just as much as if I’d haggled with the guy behind the counter.

Price Discrimination September 28, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Micro, Teaching.Tags: industrial organization, micro, Microeconomics, Price discrimination, Principles of Microeconomics

2 comments

I wear my hair short. Like, really short – it’s buzzed on the sides and scissor-cut on top, so that it’s low-maintenance, and I trim my own beard using a storebought clipper. My father-in-law does the same thing – except he pays a little bit less than I do, because he tells the barber he’s old and cheap. Why does that work?

A business, we assume, wants to make money. As such, it wants to sell its good at the highest price possible to each consumer. Consumers, though, want to spend as little as possible, to maximize the difference between their willingness to pay and the actual price they pay. (Economists call that difference consumer surplus.) Most of the time, it’s difficult to charge people different prices based on their willingness to pay. To do so requires three big elements.

First, the market has to be segmented. This means that consumers have to have different willingnesses to pay. Think about a price-sensitive consumer like my father-in-law – he’s getting ready to retire. His wife is already retired. He needs to adjust to spending less money than he’s used to. A lot of his fellow senior citizens feel his pain. Meanwhile, I’m a young(ish) guy. I teach at a community college, I have no kids, and I have a long time before I retire (so my money has a lot of time to grow). I’m willing to pay a little bit more for a haircut than he is. In addition to senior citizens, college students are often given discounts just for being students.

Second, there needs to be some element of monopoly power. My barber isn’t a monopolist, because pure monopoly is rare, but I do go out of my way to go to a place where I have a good rapport with the barber. I have a guy who cuts my hair the way I like it, and I like the atmosphere at his shop. Plus, even though I could probably shop around to find a cheaper price if I went somewhere else, I couldn’t find a price that much cheaper. Haircuts have pretty standard prices around here. That’s what the monopoly power condition is intended to enforce – if I get angsty about not getting a cheap haircut, I don’t really have other options.

Finally, the good needs to be difficult to resell. If we were talking about an oil change on my car, I might send my father-in-law into the mechanic’s shop with my car to get the senior citizen discount on an oil change. When we have a family event planned, he buys the bagels because the local place gives him a deal just for being older. Or if my mother is looking to redo the bathroom, or kitchen – my father has friends at http://www.restorationusa.com/west-palm-beach/ who’ll give them a great discount on that as well. It’s impossible, though, to resell a haircut, so I can’t use his senior citizen discount to my advantage here. Baseball and hockey tickets often offer student rush specials where you have to (theoretically) show a student ID to get the discount. Enforcing that would ensure that people with high willingness to pay didn’t buy the cheap tickets in the nosebleed section, but the open secret is that the Mets don’t really care if you buy cheap tickets, as long as you buy tickets.

If those three conditions exist, then it’s possible for a seller to charge different people different prices. Economists call that price discrimination. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, though – it means if you’re cheap, you can get a pretty good deal on some goods.

Diminishing Marginal Returns September 9, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Micro, Models, Teaching.Tags: diminishing marginal returns, graphs, Sriracha

add a comment

Close your eyes.

Well, finish reading the next paragraph first, and then close your eyes.

I am going to offer you unlimited access to something good, something useful, something tasty. That’s right – I’m going to let you have as big a bottle as you’d like of Sriracha. As long as you can carry it away, you can put as much Sriracha as you’d like on your plate of pad thai and I won’t look askance at you. No, I might even respect you. How much are you going to take?

Open your eyes.

The funny thing about that thought experiment is that everyone can picture how much they’d put on a plate of noodles. Some people might put none at all;1 others might put a little dab on the side, while still others, possibly economics professors who operate multiple blogs with self-deprecating titles, might put a truly ridiculous amount and allow the streets to run red with the blood of the non-rooster-sauces. Almost no one would ever take an unlimited amount of sauce.

That’s because, like most goods, Sriracha demonstrates diminishing marginal returns. That means that if Sriracha is meant to create tastiness, then for every extra drop of Sriracha, the tastiness increases, but the increase gets smaller. Mathematically, that means the slope is positive, but decreasing; that’s the same as saying the function has a positive first derivative and a negative second derivative. One common function used to model diminishing marginal returns is the natural log function, y = ln(x). If we assume that tastiness is logarithmic in grams of Sriracha, the graph might look like this:

Just about any good demonstrates diminishing marginal returns, and at some point you’ll have enough of a good that its marginal benefit no longer exceeds its marginal cost.

Just about any good demonstrates diminishing marginal returns, and at some point you’ll have enough of a good that its marginal benefit no longer exceeds its marginal cost.

—–

1 Those people are called wimps.

Elasticity and Demand March 18, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Micro, Teaching.Tags: demand, elasticity, intermediate microeconomics, Introduction to Microeconomics, micro, Microeconomics, Principles of Microeconomics

add a comment

The price-elasticity of demand measures how sensitive consumers are to changes in price. There are two primary formulas for that. Most commonly, introductory courses will use , where

means the percentage change. This means the numerator is

, where

is the original quantity demanded and

is the change in quantity demanded. The denominator is

. Through the properties of fractions, that ratio is equal to

, and a lot of students find that formula much easier to use.

Take note of the shape of that formula, and keep in mind the Law of Demand, which states that as price increases, quantity demanded decreases. At high prices, quantities are relatively low, meaning that a small change in price yields a relatively big change in quantity demanded. If the percentage change in quantity demanded is bigger than the percentage change in price, then demand is elastic and consumers are price-sensitive. On the other hand, at low prices, quantities are relatively high, meaning that a small change in price yields an even smaller change in quantity demanded. That means demand is inelastic.

This pattern of high prices corresponding to elastic demand and low prices corresponding to inelastic demand holds for most goods. At a very high price, firms can make a small change in price to try to encourage new buyers to buy their product, whereas at a very low price, firms can jiggle the price up a little bit to try to snap up some extra revenue without dissuading most of their buyers from purchasing the product.

A slightly more accurate formula for price-elasticity of demand is , which looks surprisingly like the previous formula but doesn’t depend on choosing an original value.

The graph in this post shows market demand in blue and elasticity in orange. Note the high elasticity at high prices and low elasticity at low prices.

Elasticity (SPROING~!) March 17, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Micro.Tags: elasticity, intermediate microeconomics, Introduction to Microeconomics, micro, Microeconomics, Principles of Microeconomics

add a comment

When we think about elasticity in the real world, we often think about the properties of things like rubber bands or the waists of sweatpants. If a solid has high elasticity, that means it’s very sensitive to having forces applied to it – so while something like Silly Putty or latex is very elastic, other materials like steel or titanium are not. A small amount of force yields a lot of deformation for Silly Putty, but not much at all for steel.

Elasticity in economics works the same way. It measures how responsive one measurement is to a small change in some other measurement.

When economists say “elasticity” without any qualifiers, they typically mean the price-elasticity of demand, which measures how sensitive purchases are to small changes in price. Elasticity, , is expressed as a ratio:

where refers to the percentage change in quantity demanded1 (the actual change divided by the starting value) and

refers to the percentage change in price (again, the actual change in price divided by the starting value).2 This leads to three cases:

– a small price change yields a big change in quantity demanded. This means that buyers of the good are price sensitive, and (equivalently) demand for the good is elastic. Note that in this case,

.

– a small price change yields an even smaller change in quantity demanded. This means that buyers of the good are not price sensitive, and demand for the good is inelastic. Here,

.

– a small price change yields exactly the same change in quantity demanded. The term for this type of demand is unit-elastic. When demand is unit-elastic,

.

It’s tempting to treat elasticity as very complicated, when it has a really simply mathematical interpretation. It answers the question “Which change is bigger – price, or quantity?”

Also interesting is the question of why some goods are demanded elastically and some are demanded inelastically. Typically, goods with many alternatives are demanded elastically. Alternatives can come in many forms. Most commonly, they’ll show up as substitute goods, or goods which you can use instead of another good. For example, bread has many substitutes (naan, grits, cornbread, rice, tortillas, English muffins….), and so if the price of bread rose significantly, you’d see many people substituting away from using bread. However, there are other forms of alternatives, too. You may see elastic demand for goods that cost a large proportion of the buyers’ income or that can be purchased over a longer timescale. A college education is an example of both of these – a small change in the level of tuition can lead to big changes in the behavior of students, who will often take a year off to earn money.

Anything with few alternatives will typically be demanded inelastically. Salt is the classic example, because it has no alternatives – it’s necessary for flavoring food, allowing our bodies to function properly, and (in the case of iodized salt) preventing certain illnesses. However, anything that is addictive (like tobacco or heroin), necessary for many uses (like cell phone plans), or difficult to switch away from (it’s not like you can put diesel fuel in your gas-engine car!) will typically have inelastic demand.

—

1 Quantity demanded means the number of goods people are willing to buy at a certain price.

2 Usually one of these will be negative and the other positive, because of the Law of Demand; economists, ever economical with their notation, simply ignore this and use the absolute value.

The Do-Nothing Alternative March 16, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Examples, Micro, Teaching.Tags: Do-Nothing Alternative, hidden choices, opportunity cost

add a comment

Consider the following situation: You are at a casino. You have a crisp new $100 bill in your pocket and an hour before your friend arrives. There are several options available: blackjack, poker, and slot machines. Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Blackjack offers a 45% probability that you will double your money over the next hour, but a 55% probability you will lose it all. Based on your understanding of statistics, you know this means you should expect to have about $90 at the end of the hour. Poker is a better proposition – since it is a game of skill, you have a 60% chance of earning an extra $50 (for a total of $150), but a 40% chance of losing all of your money. That means you can expect to have about $90 in your pocket at the end of the hour. Slot machines, to go to the other extreme, are a highly negative expected-value proposition. You stand a 1% chance of winning $1000, but a 99% chance of losing all of your money. As a result, you could expect to have about $1 in your pocket at the end of the hour.

Thinking like an economist, you quickly winnow your options down to blackjack or poker, since you cannot abide such a risky proposition. Then, however, you’re stuck – the expected values are the same. Which game is it rational to play?

Similarly, consider this problem raised in a freshman course on ethics: You are on your way out of a coffee shop carrying a double shot of espresso and a $1 bill you received as change. Two homeless people, one man and one woman, each step toward you and simultaneously ask you for the dollar. Since you don’t have any coins, you cannot split the value between the two people. Who should you give your dollar to?1

What do these two situations have in common? In each of them, you are attempting to choose between two options that result in negative consequences for you. In the gambling scenario, you have two options, each with the expectation of losing $10. In the coffee shop scenario, you have two people each asking for $1. In neither case is there a compelling reason to choose one option over the other. The underlying assumption, though, is that we must choose an option at all.

The do-nothing alternative is often (but not always) a hidden option when making choices. For example, in the gambling scenario, you have the option to literally do nothing for an hour until your friend arrives. This leaves you $100 with certainty. In the coffee shop scenario, you have the option to politely refuse each person’s request, leaving you free to keep your dollar. Not every situation allows a do-nothing option; for example, a baseball manager faced with the option of starting his worst starting pitcher or a pitcher who is usually used only in long relief cannot opt to simply start no pitcher. However, a voter who is disgusted with all available candidates may bemoan his “forced” vote for the lesser of two evils without acknowledging that he has the option simply not to vote at all. The do-nothing option is often low-cost but has low returns as well, making it a great way to avoid choosing the best of a bad lot, but a lousy choice for a firm seeking growth.

—–

1 This was met with considerable debate about the probability that the homeless woman had children.

The Good and Bad of Goods and Bads January 25, 2015

Posted by tomflesher in Micro, Teaching, Uncategorized.Tags: economics, intermediate microeconomics, Introduction to Microeconomics, Microeconomics, preferences, Principles of Microeconomics

add a comment

When students first hear the word “goods” pertaining to economic goods, they sometimes find it a little funny. When they hear some sorts of goods called “bads,” they usually find it ridiculous. Let’s talk a little about what those words mean and how they pertain to preferences.

Goods are called that because, well, they’re good. Typically, a person who doesn’t have a good would, if given the choice, want it. Examples of goods might be cars, TVs, iPads, or colored chalk. Since people want this good if they don’t have it, they’d be willing to pay for it. Consequently, goods have positive prices.

That doesn’t mean that everyone wants as much of any good as they could possibly have. When purchasing, people consider the price of a good – that is, how much money they would have to spend to obtain that good. However, that’s not because money has any particular value. It’s because money can be exchanged for goods and services, but you can only spend money once, meaning that buying one good means giving up the chance to buy a different one.

Bads are called that because they’re not good. A bad is something you might be willing to pay someone to get rid of for you, like a ton of pollution, a load of trash, a punch in the face, or Taylor Swift. Because you would pay not to have the bad, bads can be modeled as goods with negative prices.

Typically, a demand curve slopes downward because of the negative relationship between price and quantity. This is true for goods – as price increases, people face an increasing opportunity cost to consume one more of a good. If goods are being given away for free, people will consume a lot of them, but as the price rises the tradeoff increases as well. Bads, on the other hand, act a bit different. If free disposal of trash is an option, most people will not keep much trash at all in their apartments. However, as the cost of trash disposal (the “negative price”) rises, people will hold on to trash longer and longer to avoid paying the cost. Consider how often you’d take your trash to the curb if you had to pay $50 for every trip! You might also look to substitutes for disposal, like reusing glass bottles or newspaper in different ways, to lower the overall amount of trash you had to pay to dispose of.

As the cost to eliminate bads increases, people will suffer through a higher quantity, so as the price of disposal increases, the quantity accepted will also increase.