Bobby Bonilla’s Deferred Deal: A Case Study August 2, 2011

Posted by tomflesher in Finance, Macro, Teaching.Tags: annuity formula, Bobby Bonilla, compound interest, CPI, finance, macro, macroeconomics, teaching

trackback

Note: This is something of a cross-post from The World’s Worst Sports Blog. The data used are the same, but I’m focusing on different ideas here.

In 1999, the Mets owed outfielder/first baseman Bobby Bonilla $5.9 million dollars. They wanted to be rid of Bonilla, who was a bit of a schmoe, but they couldn’t afford to both give him his $5.9 million in the form of a buyout and meet payroll for the next year. No problem! The Mets sat down with Bonilla and arranged a three-part deal:

- The Mets don’t have to pay Bonilla until 2011.

- Starting in 2011, Bonilla will receive the value of the $5.9 million as an annuity in 25 annual installments.

- The interest rate is 8%.

Let’s analyze the issues here.

First of all, the ten-year moratorium on payment means that the Mets have use of the money, but they can tre at it as a deposit account. They know they need to pay Bonilla a certain amount in 2011, but they can do whatever they want until then. In their case, they used it to pay free agents and other payroll expenses. In exchange for not collecting money he was owed, Bonilla asked the Mets to pay him a premium on his money. At the time, the prime rate was 8.5%, so the Mets agreed to pay Bonilla 8% annual interest on his money. That means that Bonilla’s money earned compound interest annually. After one year, his $5.9 million was worth (5,900,000)*(1.08) = $6,372,000. Then, in the second year, he earned 8% interest on the whole $6,372,000, so after two years, his money was worth (6,372,000)*(1.08) = (5,900,000)*(1.08)*(1.08) = $6,881,760. Consequently, after ten years, Bonilla’s money was worth

at it as a deposit account. They know they need to pay Bonilla a certain amount in 2011, but they can do whatever they want until then. In their case, they used it to pay free agents and other payroll expenses. In exchange for not collecting money he was owed, Bonilla asked the Mets to pay him a premium on his money. At the time, the prime rate was 8.5%, so the Mets agreed to pay Bonilla 8% annual interest on his money. That means that Bonilla’s money earned compound interest annually. After one year, his $5.9 million was worth (5,900,000)*(1.08) = $6,372,000. Then, in the second year, he earned 8% interest on the whole $6,372,000, so after two years, his money was worth (6,372,000)*(1.08) = (5,900,000)*(1.08)*(1.08) = $6,881,760. Consequently, after ten years, Bonilla’s money was worth

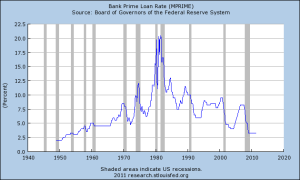

The prime rate didn’t stay at 8.5%, of course, as the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) webpage maintained by the St. Louis Fed shows. This is a monthly time series of prime rates, which are graphed to the right. The prime rate can be pretty volatile, so it was a bit of an odd choice to lock in a rate that would be effective for 35 years. As it turns out, the prime rate fluctuated quite a bit. Taking the annualized prime rate by dividing each monthly rate by 12 and adding them together, we can trace how much a bank account paying the full prime rate would have paid Bonilla:

So since his agreement with the Mets paid him $12,737,657.48 and he could have invested that money by himself to earn around $10,891,903.26, Bonilla is already better off to the tune of (12737657.48 – 10891903.26) or about 1.85 million.

In addition, we can measure the purchasing power of Bonilla’s money. Using FRED’s Consumer Price Index data, the CPI on January 1, 2000, was 169.3. On January 1, 2011, it was 221.062. that means the change in CPI was

So, the cost of living went up (for urban consumers) by 30.57% (or, equivalently, absolute inflation was 30.57% for an annualized rate of around 3%). That means that if the value of Bonilla’s money earned a real return of 30.57% or more, he’s better off than he would have been had he taken the money at the time.

Bonilla’s money increased by

Bonilla’s money overshot inflation considerably – not surprising, since inflation generally runs around 3-4%. That means that if Real return = Nominal return – Inflation, Bonilla’s return was

Because Bonilla’s interest rate was so high, he earned quite a bit of real return on his money – 85% or so over ten years.

Bonilla’s annuity agreement just means that the amount of money he holds now will be invested and he’ll receive a certain number of yearly payments – here, 25 – of an equal amount that will exhaust the value of the money. The same 8% interest rate, which is laughable now that the prime rate is 3.25%, is in play.

In general, an annuity can be expressed using a couple of parameters. Assuming you don’t want any money left over, you can set the present value equal to the sum of the discounted series of payments. That equates to the formula:

where PV is the present value of the annuity, PMT is the yearly payment, r is the effective interest rate, and t is the number of payments. Bonilla will receive $1,193,248.20 every year for 25 years from the Mets. It’s a nice little income stream for him, and barring a major change in interest rates, it’s one he couldn’t have done by himself.

[…] makes Bonilla’s deal stick out is the interest he’s getting: 8%. That’s high, as The Bad Economist pointed out a few years back, the prime rate when he signed the deal was 8.5%. The Mets probably should’ve made his […]

[…] As described earlier, to calculate prospect valuations we also need to select an appropriate discount rate that reasonably estimates how much a team would trade a win today for a win a number of years in the future. Getting this number to be fairly accurate is critical because prospects can take a while to develop and fulfill their six years of club control. Any mis-estimation of the market can compound on itself and skew our results by millions of dollars. (See Bonilla, Bobby.) […]

[…] things that makes Bonilla’s deal stick out is the interest he’s getting: 8%. That’s high, but as The Bad Economist pointed out a few years back, the prime rate when Bonilla signed the deal was 8.5%. The Mets probably should’ve made his […]

[…] makes Bonilla’s deal stick out is the curiosity he’s getting: 8%. That’s excessive, however as The Bad Economist pointed out a few years back, the prime fee when Bonilla signed the deal was 8.5%. The Mets most likely ought to’ve made his […]